Ahead of us lay a dark, dense forest abruptly impeding the endless sea of treeless farmlands. They had extended unbroken for dozens of miles to the east. Hovering above the mass of uniform trees hung deep-blue storm clouds swollen with moisture. Their menacing fingers reached for the earth. Crossing the precipice of the forest the color transformed from a brilliant blue to a suffocating, deep, wet gray. Thunder cracked through the trees, and the sky let loose a torrent of rain. We had arrived at Verdun.

Ahead of us lay a dark, dense forest abruptly impeding the endless sea of treeless farmlands. They had extended unbroken for dozens of miles to the east. Hovering above the mass of uniform trees hung deep-blue storm clouds swollen with moisture. Their menacing fingers reached for the earth. Crossing the precipice of the forest the color transformed from a brilliant blue to a suffocating, deep, wet gray. Thunder cracked through the trees, and the sky let loose a torrent of rain. We had arrived at Verdun.

One fear missing from any of our minds when we left Strasbourg hours earlier was the threat of inclement weather. In fact, we’d encountered only blue skies until now. A curvy country road cut a narrow swath through the trees. It was evident that the healthy, new-growth forest was sewn at a single point in time, exactly 100 years earlier. Any vegetation that was once here before then was obliterated, blasted into a trillion splinters by nearly a full year of devastating artillery fire. Peeking through the trunks I could see the clean, grassy forest floor pockmarked by innumerable rolling craters of all sizes. It was as if the surface of the moon had suddenly come to life with sprouting organic growth.

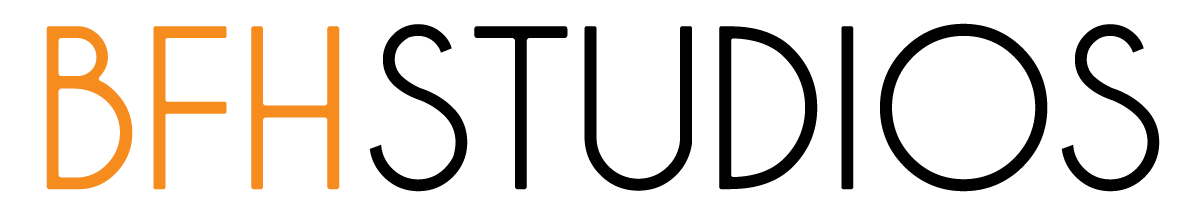

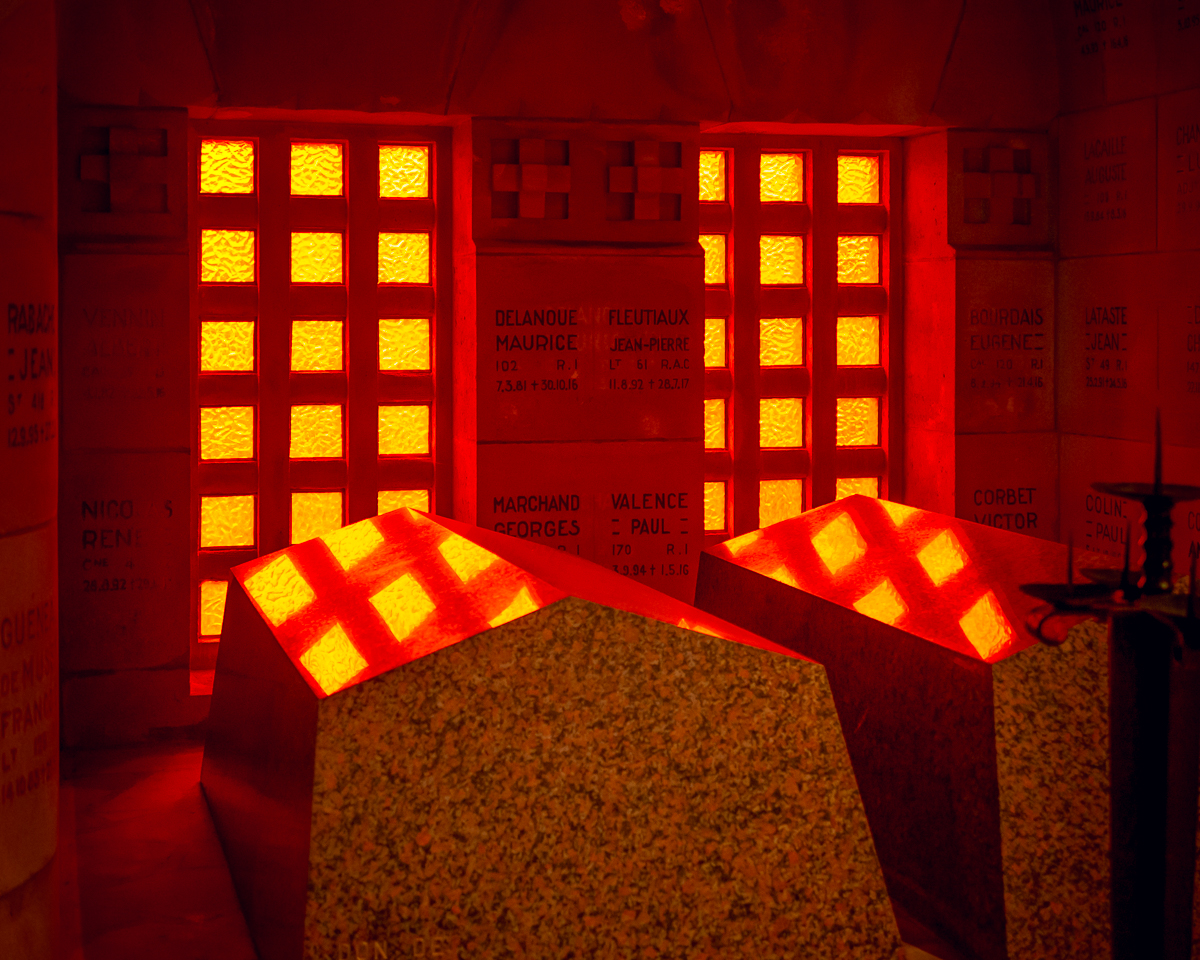

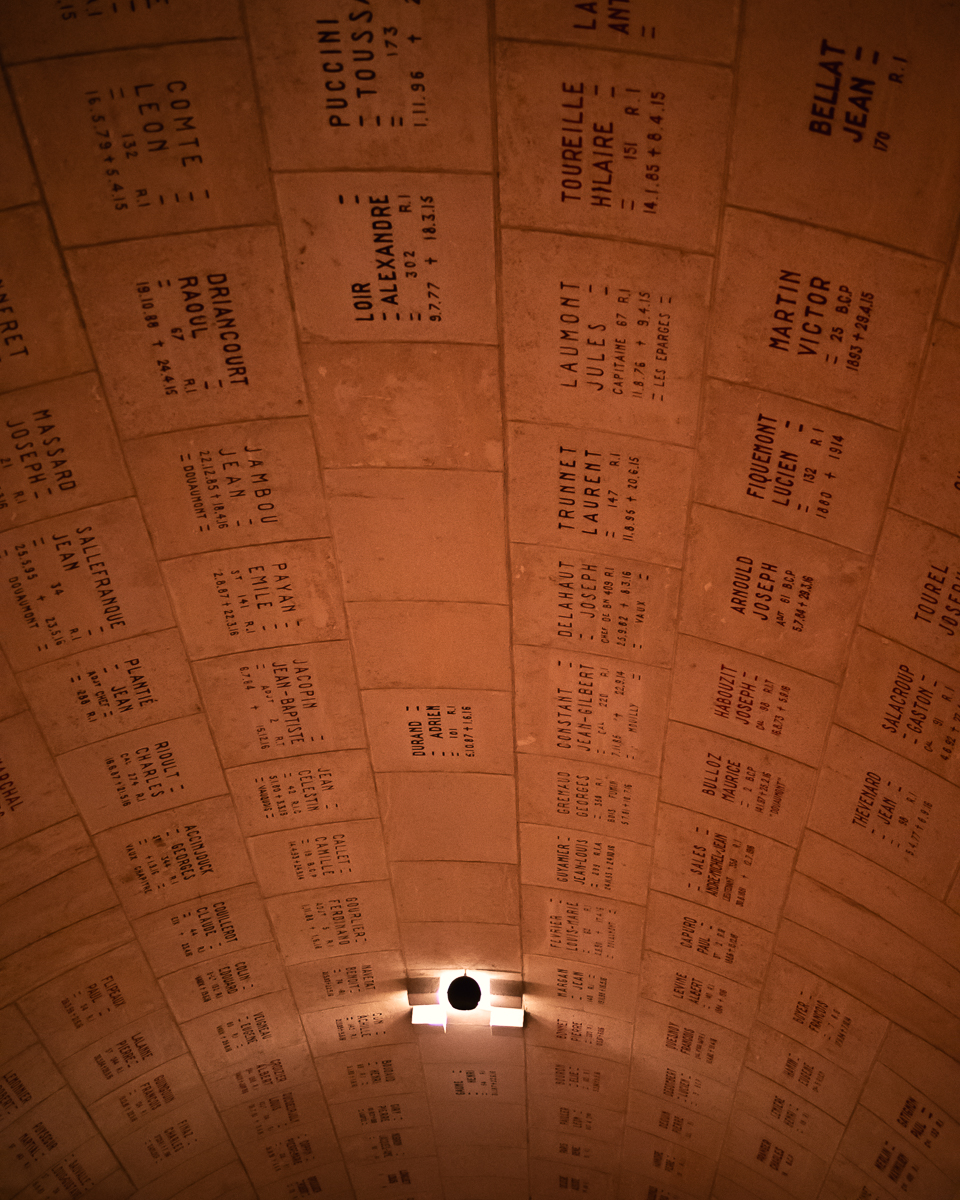

The wooded road eventually gave way to a large clearing studded by an ominous exclamation-point-straight tower in the shape of an artillery shell – only this one was pointed to the heavens and not toward the Earth. In the foreground, 100,000 crosses in perfect rows, each with a splattering of red provided by cut flowers, marked only a portion of the WWI victims that perished here. One hundred years ago this idyllic forest was hell on earth. Looking across the rain-washed field among the trees it was difficult to comprehend the horrors that took place here.

In the most senseless war the world ever bore witness to, Verdun was the largest and longest of its battles. Named for the nearby town and situated on a long traditionally strategic elbow between France and Germany the region and its impregnable forts became the bloody stage in a conflict motivated by mass slaughter and tactics of wholesale shelling. Frontline soldiers were driven underground into muddy and squalid trenches and forced to go “over the top” of their refuges for hopeless bayonet charges. When the smoke cleared 300 days later, more than 300,000 young French and Germans had perished under the most ghastly circumstances – one thousand a day for nearly a year. Caught in the crossfire tens of villages were wiped from the map and nature has since taken their place.